“I must perish like a Roman, Die the great Triumvir still”

- Mar 21, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 26, 2024

By Taylor Akers '24

Prepared for Historic House Museums course 305, Museum Studies department.

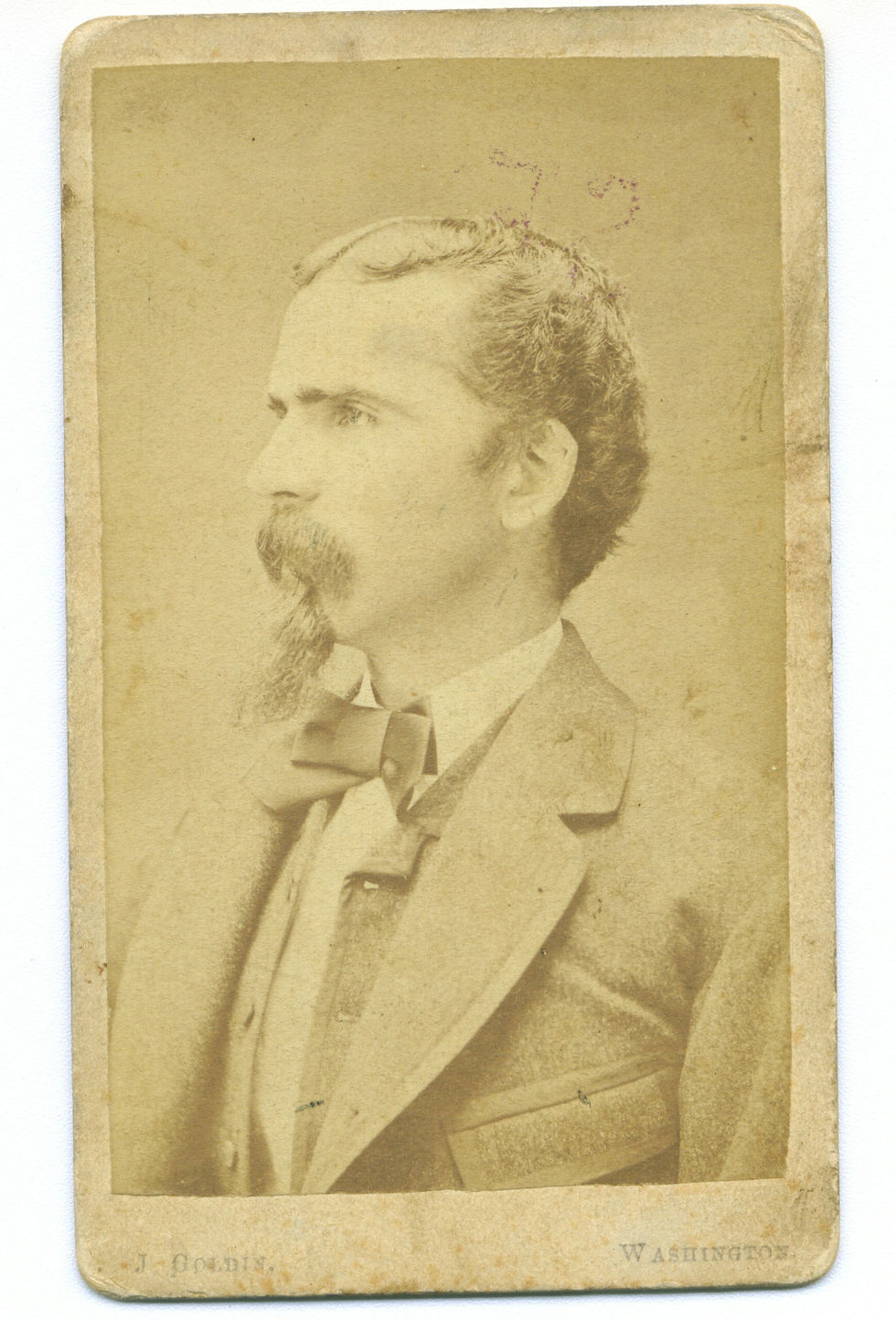

James Risque Hutter (October 22, 1841 - June 15, 1923), called by his friends and family "Risque," was born and died at Historic Sandusky in Lynchburg Virginia. Risque would obtain many titles from the military throughout his long years of service. In July 1860 he graduated from the Virginia Military Institution (VMI) and a year later on May 16th, 1861, he would join the Confederate army as Captain of Company H, 11th Virginia Infantry. In 1863 he would go on to be promoted to Major, followed by Lieutenant Colonel in 1864 and Colonel in 1865. Risque would also spend a considerable amount of time imprisoned on Johnson’s Island, a Union POW camp located on Lake Erie.

Risque and his company would arrive to Gettysburg at sundown on the evening of July 2nd,1863. The next day (July 3rd) during Pickett's famous charge, he would be injured by a bullet that grazed his chest. Although not life threatening, this would result in Risque being captured by the Union forces on “Cemetery Hill.” From there he would be transported to Johnson’s Island off the coast of the Sandusky Bay in Ohio near Lake Erie, that was 300 acres in total. The island had been purchased by Leonard B. Johnson in 1852, which he then named after himself and would later rent half of the island to the US military for $500 year. After the war, the US military would relinquish their rent from the island, returning it to its original owner.

Risque would be held on Johnson’s Island until Jan 27, 1865, when he would be exchanged for Union POWs. His freedom would be short lived. He was recaptured at “Five Forks,” in VA on April 1st, 1865. He would once more be transported to Johnson’s Island where he would remain until Jul. 25th, 1865.

“The Book of Common Prayer,” 1863, that Risque Hutter had with him during imprisonment. Historic Sandusky Archives and Collections

While imprisoned at Johnson’s Island, Risque Hutter would also go on to purchase a blank book to which he would go on to get the signature of every inmate on the island. He would also take time to draw a detailed map of the buildings in the prison camp.

Map drawn by Risque Hutter while being imprisoned at Johnson’s Island. Historic Sandusky Archives and Collections

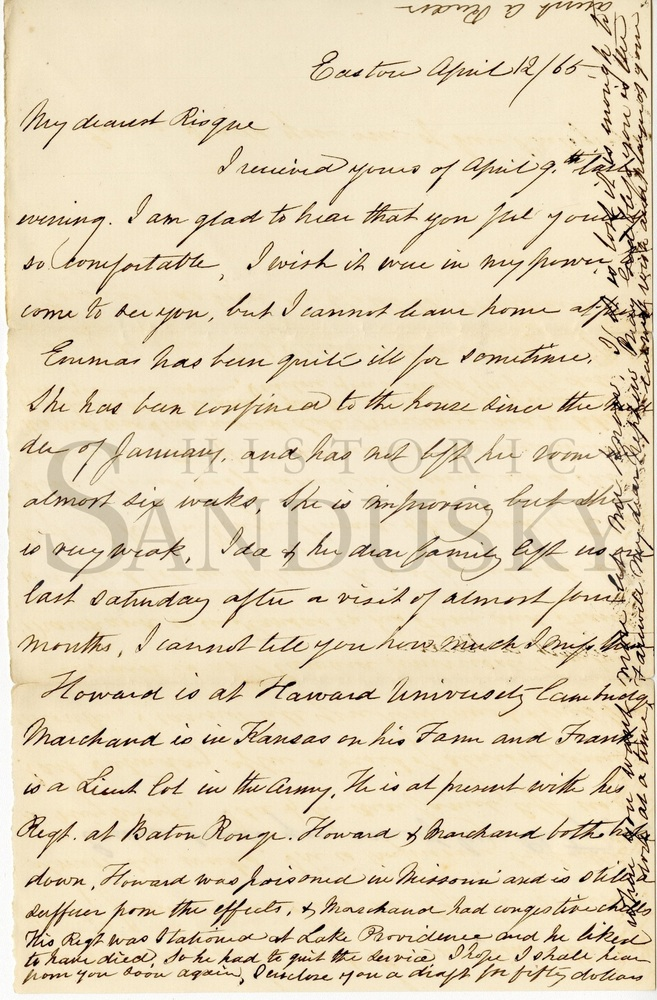

Although he was a prisoner, Risque Hutter was still able to receive mail and packages from his family members, much like others that lived on Johnson’s Island. On several occasions his mother, sister, and aunt, would send him letters to see how he was faring and if he received the packages that were sent. At some point he would receive a letter from his aunt, Fredericka Amalia Hutter Reeder who informed him that she had tried and failed to move him to a more appealing POW camp. Most prisoners would receive clothing that they would either trade or sell with other inmates. The US government was supposed to supply adequate clothing for the Confederate Generals, but did not always follow through with this promise, leaving others to take pity on their fellow bunkmates.

April 12, 1865 letter from Fredericka Amalia Hutter Reeder (1810-1878) to her nephew, Risque Hutter. Historic Sandsusky Archives and Collections.

During his stay at Johnson’s Island, Risque Hutter would keep an in-depth detail of what life on the island consisted of. There were a total of 13 blocks or frame buildings. Each of these was 90 ft long by 25 ft broad, having both upper and lower levels. These buildings would consist of 6 in a row, each facing the other. There was a total of 27 beds/bunks raised one above the other, 3 deep toward the ceiling. The Island had been specifically chosen by the US government due to its location. Much like a modern day Alcatraz, Johnson’s Island was impossible to escape from. The isolation prohibited anyone who tried to escape from getting far.

On top of this, the island was near several important Ohio cities, railways, and water transportation ways. This made it easy to acquire the necessary food needed to feed those living on the island, along with being able to easily acquire supplies needed to build. During its first several years, Johnson’s Island accomplished what it had set out to do. Many exchanges were made, Confederate POWs for Union POWs. This seemed to be short lived though. The island was only designed to hold 1,000 prisoners but would eventually swell to a total of 3,256 prisoners by 1865. Over crowding and poor sanitary conditions would result in illness. During its 40 month operation a total of 200 prisoners would die. Most would be forced to agree to an Oath of Allegiance to the United States. By September 1865, those few that remained on the island were transported to other prisons.

Photo of the Prisoner Of War stockade, Johnson’s Island, Sandusky Bay, Ohio. A remarkable photo most likely taken from a boat on a very calm day. Date not known. Note lack of guards or prisoners. (Sandusky Library, Charles E. Frohman Collection) Johnson’s Island database

Company of the Hoffman Battalion at roll call. The barracks building was the same type built for the prisoners. The lean-to buildings on each end were kitchens. In the background is a portion of the stockade wall showing the parapet used by the guards while on duty. (Sandusky Library, Charles E. Frohman Collection). Johnson’s Island Database.

Before conditions became incredibly dire, many inmates would start their own businesses. Laundry was one of the best ways for these men to get revenue of their own. This could consist of actual money or other items that may be of use to them. Archaeology done at Johnson’s Island has proven that this business was done mostly outside. Many confederate buttons have been found in what was once the courtyard to the prison. It has also been found that another easy was for these prisoners to make money was by creating things using objects around them.

Enlarged image of Shield made from hard rubber button and inlaid with silver cross and mother of pearl. Button marked Goodyear S P. (R. Ibos Collection) Johnson’s Island Database.

After finally gaining his freedom, Risque Hutter would make a living by being a surveyor and farmer. He would go on to marry his half cousin Charlotte Stannard Hutter at Poplar Forest on October 30, 1877. They would go on to have a total of 10 children.

James Risque Hutter in his later years at Sandusky House, 1914. Historic Sandusky Archives and Collections.

Taylor Akers is a senior at University of Lynchburg, graduating in May 2024. She is a history major and museum studies minor. She currently works at the National D-Day Memorial in Bedford, Virginia, as an assistant site manager, as well as working at Historic Sandusky in Lynchburg, Virginia. She plans to get her masters in Archival Studies in the future.

Bibliography

“Civil War Era.” Johnson's Island Preservation Society. Accessed April 29, 2023. http://johnsonsisland.org/history-pows/civil-war-era/.

John Goldin, photographer, “Photograph, James Risque Hutter (1841-1923),” Historic Sandusky Archives and Collections, accessed April 19, 2023, https://historicsanduskyarchives.omeka.net/items/show/97.

“The Book of Common Prayer, 1863, James Risque Hutter (1841-1923),” Historic Sandusky Archives and Collections, accessed April 19, 2023, https://historicsanduskyarchives.omeka.net/items/show/35.

“Letter, 12 April 1865, Fredericka Amalia Hutter Reeder (1810-1878) to James Risque Hutter (1841-1923),” Historic Sandusky Archives and Collections, accessed April 19, 2023, https://historicsanduskyarchives.omeka.net/items/show/112.

Unknown photographer , “Photograph, James Risque Hutter (1841-1923) on side portico of Sandusky,” Historic Sandusky Archives and Collections, accessed April 19, 2023, https://historicsanduskyarchives.omeka.net/items/show/43.

She is employed as an assistant site manager at the National D-Day Memorial in Bedford, Virginia, geometry dash and at Historic Sandusky in Lynchburg, Virginia. In the future, she wants to pursue a master's degree in archival studies.